Deep Equality in the Face of Belligerence

6 February 2026

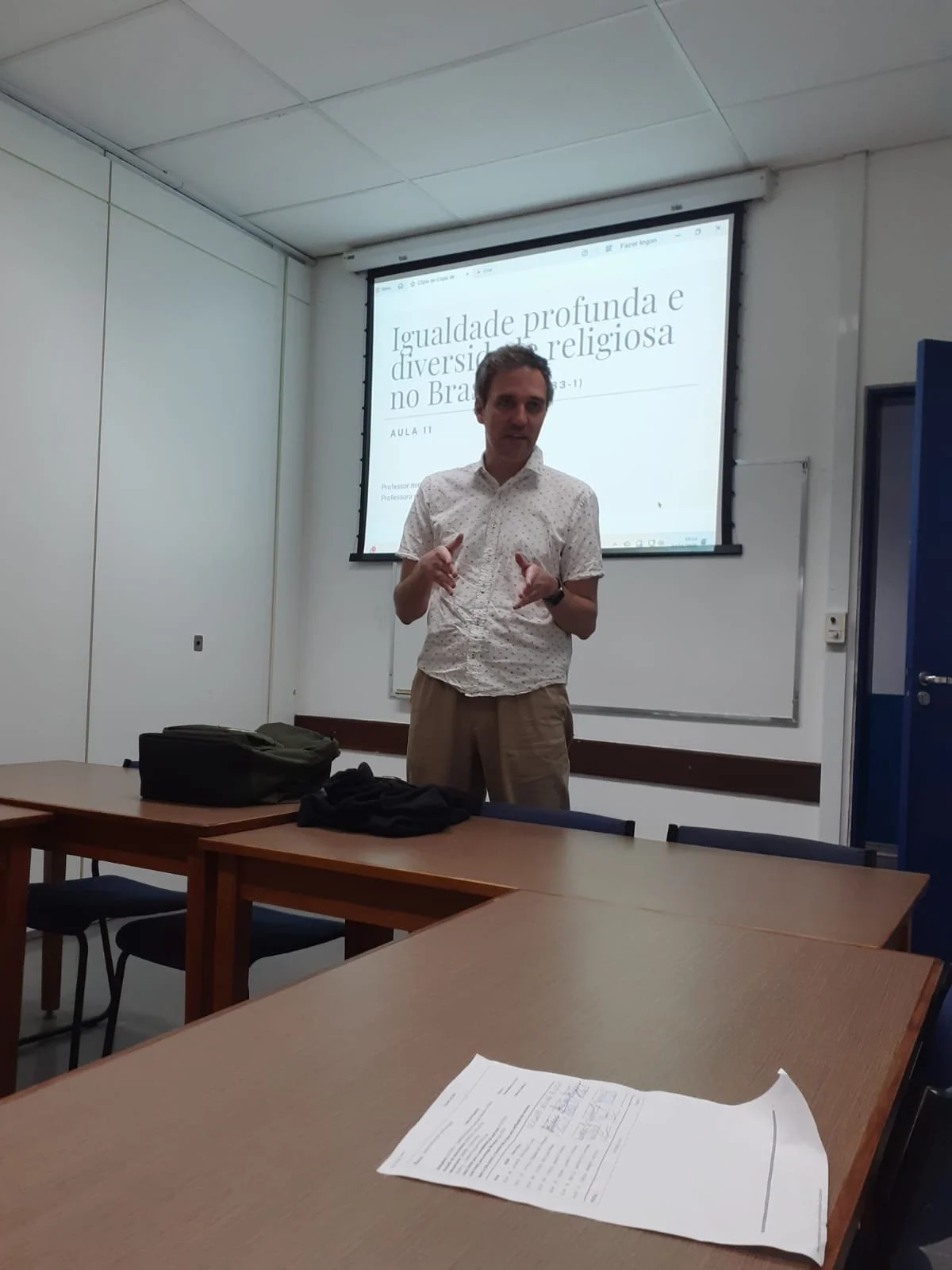

Dr Guilherme Borges, a postdoctoral researcher with the Social Repair project, developed an analytical, non-normative perspective on Lori Beaman’s concept of deep equality. In this blog, he discusses his experience of presenting this perspective to a Brazilian audience.

The Course on Deep Equality

The concept of deep equality has been used in countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms for the negotiation of diversity in these national contexts. Drawing on the analytical tools proposed by Lori Beaman (2017), scholars in these countries seek to shed light on acts of “living well together” that happen beyond state prescriptions and beyond the very idea of tolerance.

By contrast, work employing this analytical framework remains rare in the Global South. In response to this gap, I organized and taught the course Deep Equality and Religious Diversity in Brazil at the University of São Paulo (USP). Over the second semester of 2025, the course explored analytical possibilities of deep equality in order to observe, in the Brazilian context, everyday practices of coexistence that transcend juridical–political determinations.

Deep Equality as an Analytical Tool

One of my main concerns when introducing the notion of deep equality to my students was to avoid sounding naïve or overly anchored in Global North assumptions. Accordingly, the strategy I adopted was to explore this notion not as an ideal to be achieved, but rather as an analytical tool capable of refining our understanding of social interactions in contexts of diversity.

To this end, I identified that deep equality emerges from two central and interrelated premises. The first is the existence of a significant gap between official models of diversity management—typically formulated within the realms of public policy, law, or major public debates—and the ways in which social actors, in their everyday practices, actually deal with difference in interpersonal interactions. The second premise, in parallel, concerns a recent limitation of the social sciences: by placing excessive emphasis on these official models and on large-scale controversies, they risk to some extent losing their capacity to attend to what unfolds within ordinary practices of social life.

In light of this dual diagnosis, the concept of deep equality allows the researcher to shift their analytical gaze toward everyday practices of interaction among diverse people. This shift makes it possible to identify a potential prevalence of relations of mutual recognition and cooperation—cooperative relations that are, at the very least, far more common than academic frameworks tend to assume. These “non-events”, however, rarely become visible precisely because they do not generate public controversy.

Deep Equality ≠ Social Cohesion

Another point that I emphasized, concerns the distinction between deep equality and the Durkheimian idea of social cohesion. Deep equality does not refer to a durable state, nor to a phenomenon that manifests itself at the macrostructural level. Rather, deep equality is fragile and situated, emerging in specific moments of suspended hierarchies, within ephemeral interactions that are oriented neither toward open conflict nor toward mere tolerance. The contribution of Beaman’s concept lies precisely in enabling these interactions to be identified, described, and named.

In Closing: Looking Beyond Conflict

This “discreteness” of cooperative relations requires researchers to unlearn certain analytical dispositions in their craft—particularly the tendency to take conflict as the privileged starting point for analysis—and to reorient their attention toward forms of cooperation that silently permeate social life.

My emphasis in the course taught at USP was not on downplaying the presence of conflict. Rather, it was on recognizing the need to also address social interactions grounded in practices of cooperation. One issue raised by Brazilian students concerns how it is possible to speak in terms of deep equality in their national context, given the pervasive belligerence in Brazil. My response was not to set aside these tensions, but to stress that our understanding of social reality becomes more precise and nuanced when, alongside the recognition of disputes, we also acknowledge that such antagonisms do not erase cooperative relations.

In this way, without denying the analyses of conflict that are so necessary in countries such as Brazil, deep equality allows further nuance by also making visible cooperative dynamics embedded in ordinary interactions.

Dr. Guilherme Borges with students who took the Deep Equality course at the University of São Paulo. From left to right, standing: Sabrina Guimarães, Elisabete Montesano, and Sofia Correia; seated: Luciana de Oliveira and Wesllen de Souza.

References

Beaman, Lori G. (2017), Deep Equality in an Era of Religious Diversity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.